It was a fun weekend. Kyle and I finally did the thing where you pick a movie that feels perfectly engineered for a rainy October 31st. You’ve Got Mail, released in 1998.

It’s a beautiful montage of New York City in the fall, the charm of dial-up internet, coffee, and bookstores. I was surprised to learn that Kyle (brace yourself) had never seen it.

So we put the ambient lights on, poured out some red wine, grabbed a blanket, and settled in for one of the most heartwarming films ever made.

The part where I briefly recap the plot

- Kathleen Kelly runs a small independent bookstore called The Shop Around the Corner that she inherited from her mother. Joe Fox is opening a massive Fox Books superstore that will inevitably put her out of business.

- They meet anonymously online (radical in the 90s) and fall for each other through adorable emails, neither knowing who the other person is in real life.

- She hates him IRL (he’s literally destroying her livelihood). But they love each other on AOL (where they get to play fictional characters that omit the details that would make them incompatible).

- Eventually Joe figures out the truth first. He slowly and carefully wins her over in person while she’s still oblivious to his online identity.

- Kathleen’s bookstore closes, but by the end she’s moved on and fallen for him anyway. The movie ends with a blind date in the park, and she realizes the person she’s been emailing all along was right there in front of her.

- Somewhere over the rainbow plays, a golden retriever comes running along, they kiss.

It’s a perfect tribute to the 90s with its rom-com earnestness and the belief that love can smooth over anything, including the corporate destruction of small businesses.

Wait, something’s wrong

When the credits started, something felt off. I sat there waiting for another scene that I was sure existed: Kathleen reading to a circle of kids in a miniature version of her old bookstore, recreated inside Fox Books.

A little corner with twinkle lights and a sign that said “The Shop Around the Corner.” I could see it so clearly: the kids sitting all around her, Kathleen reading a book to them.

I looked it up: How does You’ve Got Mail end?

Things got very weird very fast. Apparently, the ending I remember doesn’t exist. It’s not real. It isn’t some director’s cut, post-credit scene or anything.

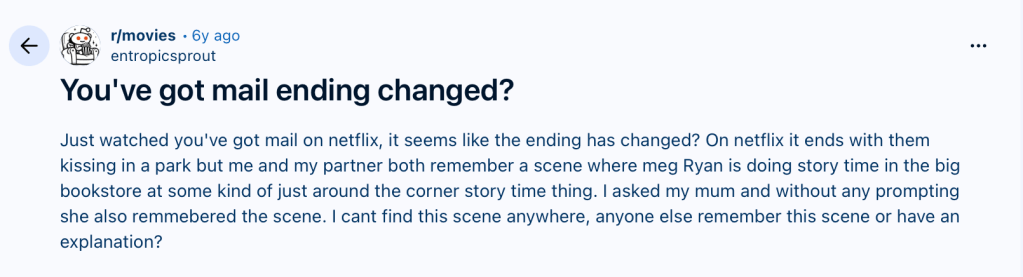

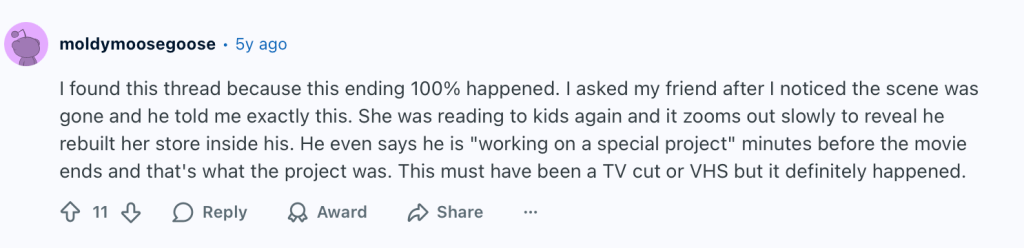

Then things got even weirder. It wasn’t just me that remembered the ending that way.

There were dozens of people who remembered the exact same scene. Some remembered it as a post-credits scene. Others remember it after the kiss at the end. Some people remembered it with the sign ‘Shop Around the Corner’ like I did, others didn’t have the sign. Someone else remembered the camera pulling back to reveal Joe watching from a distance (I think that’s how I remember it too).

BUT THE SCENE DOESN’T EXIST. It never did.

After learning about this, I uploaded a poll on my Instagram story because research, and I asked people how they remember the ending.

Seventy-four people voted. 54% picked Meg Ryan reading to kids in his store. 46% picked them meeting in a park.

More than half??? More than half the people who responded remembered the exact same fake scene that I made up in my brain???

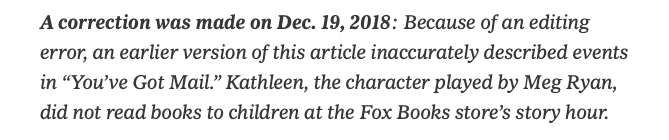

Okay fine, maybe my followers are just collectively bad at remembering movies. Unlikely but not impossible. But then I found out that a movie reviewer who works for the New York Times, whose literal job is to review movies, made THE SAME MISTAKE.

She wrote about Kathleen reading to children at Fox Books’ story hour. The Times had to issue a correction: “Kathleen, the character played by Meg Ryan, did not read books to children at the Fox Books store’s story hour.”

Even a professional film critic, whose job is to watch movies carefully, remembered a scene that never existed.

So it’s not just me. It’s not even just my 70 Instagram followers. It’s critics, it’s strangers on the internet, it’s apparently a decent chunk of people who’ve seen this movie.

We all remember the same thing. And it never happened.

This has a name apparently

The Mandela Effect. It’s basically shared false memories. Collective delusions. Situations where large groups of people confidently remember something that never happened.

It started with someone called Fiona Broome, who discovered in 2009 that she and many others “remembered” that Nelson Mandela had passed away in prison in the 1980s, even though he was actually released, became president of South Africa, and died in 2013. So many people remember the false version of events that they named it after him.

The internet has since cataloged hundreds of these. Here are some classics:

“Luke, I am your father.” Except Darth Vader never says this. The actual line is “No, I am your father.” But we all quote it wrong because adding “Luke” makes it clearer out of context. Our brains optimized for clarity over accuracy, seems fair.

The Monopoly Man’s monocle. He’s never worn one. Not once. But since he’s dressed up like a cartoon rich guy, we just added it in.

Britney’s mic headset in “Oops!… I Did It Again.” She never wore one in the music video.

Maybe we watched her perform it so many times with the headset that our brains retroactively edited it into the original video.

What’s interesting about these examples is that they’re pretty logical. We’re not remembering random nonsense. We’re remembering the versions that maybe should exist, the stuff that makes more sense.

Okay but WHY though?

When there’s stuff I don’t understand, I usually first turn to the dead philosophers. They’re my favorite bunch. It doesn’t matter how long ago it might be, they’ve thunk up some thoughts that are relevant to my thinks today. And they can’t judge me for asking dumb questions because they’re dead.

In 1896, French philosopher Henri Bergson discussed something that neuroscience is only now catching up to. He was trying to figure out the relationship between body and mind, and he used memory as his way in. His big radical claim: memory isn’t stored in your brain.

The brain’s job isn’t to hold memories like some kind of biological hard drive. The brain’s job is to help you make sense of the present by pulling in relevant memories when you need them.

Bergson said there are two types of memory. First, there’s habit memory (or what we call muscle memory). Stuff like how to ride a bike, how to type, your route to work. It’s reliable and mechanical.

Then there’s pure memory, which is the interesting one. This is memory of specific moments. Memories that represent the past as past, that you consciously recognize as things that happened (e.g. the movie ends with Meg Ryan reading to kids in the upstairs section of the bookstore).

What Bergson says is essentially this: Pure memory is creative. Not like artistic, good at interpretive dance and painting type of creative. Creative like actively creating something fresh each time.

He also calls it utilitarian memory because it involves action. When something happens in the present, your memory kicks in and goes: Hey, here are all the times something similar happened before, here’s what came next, here’s what you should probably do. It’s giving you decision-making material in real time.

This sounds very handy and convenient, and it usually is. But it can also be a bit glitchy. When you remember something, you’re basically assembling it using whatever you currently know, feel, and believe. You’re using your present emotional state, your current understanding of how things work, your expectations about how things should go. The original event is there somewhere, sure. But each time you remember it, you’re basically rebuilding it.

This is why eyewitness testimony is so unreliable. This is why siblings remember the same childhood event completely differently. We’re not lying, and we’re not necessarily forgetting. We’re creating. Each memory is a shiny act of imagination, constrained but NOT determined by what actually happened.

Okay but how did we all construct the SAME fake version here?

Here’s where it gets weird. Bergson explains why *I* invented a scene. He doesn’t explain why all of us invented the SAME scene.

I’m not sure why, honestly. Is it because the real ending of You’ve Got Mail felt so abrupt? Like she just says “I wanted it to be you” and that’s it? It resolved the romance but left the loss unaddressed. She lost her life’s work, her bookstore, the place that housed so many memories with her Mom, her staff lost their jobs, and in exchange, she gets… a boyfriend. And HE’S the guy responsible for all those losses?

Look, I’m not a fun-sucker. I know it’s the 90s, I don’t expect feminist masterpieces from romcoms. I still love this movie. But even with 90s rom-com logic, that ending leaves something unresolved.

The scene we all mis-remember fixes that in a small, imperfect way. It gives Kathleen her bookstore back, even if it’s only a corner. She’s reading to children again, doing what she loves. The love story and the bookstore both survive. She gets to have her cake and eat it too.

I think maybe all of us wanted that for her? And so we all just… invented it? Without even discussing it with one another? We took the movie we got, and mentally added in the scene we needed. And then forgot that we made it up. We just said yes, this is how it ends.

Here’s what helped me make sense of this collective hallucination: I think our brains are working like a large language model. Just like ChatGPT (or the LLM of your choosing), our brains are trained on massive amounts of data, and when it hits a gap or encounters something it can’t make sense of, it doesn’t just leave that puzzle piece empty.

It generates something that seems right based on the patterns it has learned, even when it’s not true.

In this context, our training data would be all the stories we’ve absorbed. We’ve probably read the same books, watched the same movies, heard the same narratives, fairytales, and plot lines. We’ve learned the same patterns: the girl gets the guy and the dream, and they live happily ever after.

So when You’ve Got Mail ends and something feels off because the movie set up two conflicts and only resolved one. Our brains kicked into that creative memory mode that Bergson talked about, and we generated the missing piece.

I think it’s the SAME missing piece for all of us because we’re all working from the same cultural library, using what we know about satisfying endings and what we want for her character.

That’s why sometimes, we can’t tell the difference between what we saw and what we expected to see.

What this means (or doesn’t)

I don’t want to turn this into a grand lesson about truth and memory and what it all means for our lives. You can come up with that on your own. But it is worth sitting with how easily we can be this wrong, thisss confident, and THISSS collectively synchronized in our wrongness.

We think of memory as private property. MY memories, my experiences, my truth. But it could be more collaborative than that. We’re all writing and rewriting stuff together like one big messy group project, and nobody’s keeping track of the original. That should probably unsettle us a little. If dozens of strangers can swear they saw the same fake movie scene, what else are we collectively misremembering?

Zoom out to history and this gets genuinely scary. The stories countries tell about themselves, the villains we agree on, the heroes we collectively invent. Mass false memories are how we construct entire narratives about who wronged whom, who deserves what, which version of events is “true.”

But let’s come back to the movie, because honestly that’s more manageable to sit with.

Nothing’s really changed for me since I discovered this whole thing. I still love You’ve Got Mail. I’ll still watch it again, many, many times. I’ll probably still cry when that golden retriever comes running across the grass as Somewhere Over The Rainbow plays.

Kathleen will cry, too. Joe will say softly, “Don’t cry, ShopGirl.”

And she’ll tell him, “I wanted it to be you. I wanted it to be you so badly.”

And I’ll think of everyone who remembered the ending that never happened, because I suppose we all wanted the same thing for Kathleen: We wanted it to be her too.

Leave a comment