Wow hi it’s been a brief minute since I published anything. July 2025 has to have been one of my all time favorite months so far. Like in life. It was full of the most wholesome, special moments with family and friends, and every time I thought about pulling myself away to write, I decided nah. Leave the laptop alone. It’s quite a privilege to have a life that you don’t want to pull yourself out of, and while all seasons of life aren’t that way, when they are, I choose to soak it up.

This essay is a little different from my usual stuff. Most of the time, I’m looking at the world, picking something apart, trying to make sense of it in a way that’s hopefully useful to other people. This one is more tangled. I’ve had versions of it sitting in my drafts for the last four or five months. I kept coming back to it, adding a paragraph here and there. I was never quite sure if I’d be able to land the whole thing.

Part of why it’s taken so long is because I hate the feeling of telling people what to do or how to live. That’s not my lane. The internet already has more than enough people declaring what’s right, what’s wrong, what’s moral, and what’s idiotic.

So instead, I’ve tried to write this more as an essay to myself of things I’ve noticed, patterns I’ve caught in my own thinking, lessons I’m trying to hold onto. They may not hold up forever, but for now, they feel worth writing down. Some of the early examples are about parenting, but I promise this essay wasn’t written with only parents in mind.

It all started with a conversation with a few friends around the start of the year. All of us were in slightly different stages of raising little kids, and we were talking about how MUCH we used to panic about things. Missed naps, screentime, what they’re eating, whether it’s a bad thing to feed them to sleep. Now, a couple of years later, the general approach was: eh, they’ll live.

One of us (I promise it wasn’t me) said something about how parenting gets so much easier once you just learn to… chill out. And everyone agreed. And while “chill out” has never been helpful advice in the history of human conflict resolution, I realised maybe it should be. Only because it’s true

For those who know me personally, “chill” has never been a dominant personality trait. I’d been okay at hiding my neuroses, but that was only until I was pregnant. That’s when I became painfully aware of just how non-chill I really was. That’s when I truly let out the crazy.

I’d heard about moms who think they’re better than everyone else. The kinds who have something to say about your birth plan, brag about their natural deliveries, or judge you if you formula-feed. I remember thinking, with absolute certainty: I will never be like that.

I told myself I understood that people made different choices because they had different circumstances. I’d even say it out loud if the topic came up: Every parent has to find what works for them, there’s no one right way to do it. I was proud of that stance, it made me feel reasonable and fair-minded. I thought it made me immune to the weird competitiveness that seems to come free with life in general, not just parenting.

But then the actual baby arrived.

Life became a constant decision tree, and every choice felt weirdly high-stakes. Unlike most choices, you didn’t get a week to think things through. There was no time to “do the research.” Sometimes you had thirty seconds while the baby was screaming. Would I push through another breastfeeding attempt or give the bottle? Spend my one free hour pumping, or take a nap so I could survive the day? Put her down in the crib and risk her waking instantly, or keep holding her until my arm went numb? None of these questions had universal answers, but in the thick of it, they all felt urgent. And whichever one I chose, I knew I was trading off the other.

It’s worth saying out loud that a lot of these early decisions DO cost you something, whether it’s time, sleep, or sanity––parts of yourself you didn’t think were negotiable.

For me, it started with breastfeeding, where pretty much from day one, when you have ZERO idea how to do any of it, you have to push through incredible pain to persevere, and feed your baby.

Unlike most things, breastfeeding actually gets a good deal harder before it gets easier. You and your baby both have to learn how to do it, and neither of you has the faintest idea of what’s right or wrong. There’s pain, struggle, kicking, crying, fussing, and that’s just you. The baby’s also having a bad time.

So what do you do? Push through the pain and hope it gets better? Switch to formula so you can breathe? Pump? All of these choices are valid, but you have to choose one.

I struggled with feeding for about six weeks, at which point I decided to contact a lactation consultant and fix things. In the thick of recovery and postpartum, six weeks is a long time to struggle with a newborn. But I’d already decided to give it my best shot, so I persevered through the pain, learnt how to do things right, and managed as best I could. And when I FINALLY got to the point where feeding felt “normal,” I felt something I didn’t expect.

I felt better than others.

This is distinctly different from feeling proud of myself. I felt like I’d proved something about my character that other people hadn’t. Like the fact that I’d stuck it out when I was miserable meant that I was tougher, more committed, maybe even more selfless. Now obviously I didn’t say any of this out loud because I didn’t need to. I still said all the right, nonjudgmental things in conversation with other parents. But inside, I had decided there was only one right way to do it, and I had done it.

And before you decide I’m a terrible person, you should know: everyone does this. Not all mums. Everyone.

One of my all-time favorite writers, Haley Nahman, calls this the “purity vortex.”

The purity vortex is what happens when you’ve made a hard, high-stakes choice, especially one that cost you something. In order to live with your decision, you need to decide that it’s the ONLY correct choice. It’s not enough that it was right for you, it has to be universally right. Because otherwise, what did you put yourself through all that for? You can’t just say, it was one path of many. That would mean that your suffering wasn’t strictly necessary. And if the suffering wasn’t necessary, then you might have been wrong to choose it. And who wants to be wrong? Nobody. So instead, the alternative has to be wrong.

“In the face of these choices,” she writes, “we often painstakingly construct worldviews that support the choice we’re trying to make to get us over the hump of our own resistance. And we do this so well that we temporarily render any other choice ridiculous.”

It happens across all kinds of big, identity-shaping decisions: quitting your job, starting a new eating habit, staying in a difficult relationship, leaving a difficult relationship, becoming sober, leaving your hometown.

When you make a choice that feels risky or painful, you have to psych yourself up to take the leap. For a while, you have to believe “there is only one thing to do.” That conviction is what gets you through. And don’t get me wrong, it’s a good thing. But if you hang on to it for too long, it can morph into ongoing certainty not just about your own life, but about everyone else’s.

The purity vortex makes your choice not just yours, but THE BEST possible choice. That makes you the kind of person who makes the best possible choices. That keeps your self-image intact.

In less than three years of parenting, I can already look back and see how many of my “firm positions” have shifted. I feel incredibly stupid sometimes when I realize how much of my life has been driven by arrogance I didn’t even recognize as arrogance because it was hiding behind words like values and principles.

Of course with the purity vortex, once you start noticing it, you can’t unsee it. It’s everywhere.

The person who finally left India and now insists there’s no future for anyone who stays.

The couple who just bought their first place and now think renting is throwing money away.

The co-worker who left their job to freelance and now sees every career frustration as a sign you should quit too.

The couple who swears the only way to have a wedding you won’t regret is to keep it small, because that’s what they did and it was perfect.

The parents who think sleep training is kindness, and the parents who think it’s cruel.

The people who switched up their diet and now think everyone else is eating all wrong.

But that’s the thing, most of these people aren’t wrong. Their choice probably is right for them, given their circumstances and limitations. The trouble is how quickly “this worked for me” turns into “this is what works.”

It’s easier to believe there’s one correct path than to sit with the idea that life is mostly a series of trade-offs, and that different people can make different decisions without one of them being wrong.

We like to think our beliefs come from calmly weighing the facts. More often, it’s the opposite. We start with the story we want to tell about ourselves, then collect the facts that fit. We want to be good, competent, reasonable people. We want to know we’re doing life right. And when someone makes a different choice, it pokes at that self-image in ways we don’t even want to admit. Especially if their choice seems to work.

I don’t want to paint us out to be horrible people, because that isn’t the case. What’s humbling and also kind of gross is realizing how much of this is just self-preservation. We NEED to hold onto these beliefs for ourselves. It’s hard to make hard decisions otherwise. It’s even harder to stick with them.

For what it’s worth, I’ve worked hard to chip away at some of my own rigid ideas about parenting. I have a lot of respect for people who’ve made choices different from mine, because I know none of them have it “easy.” Parenting doesn’t really offer that option to anyone.

I’ve already walked back plenty of my own “absolute” life decisions.

I once swore I’d never leave Bombay. It was my city, my identity, my whole network. And now I live in Goa. I’ve swapped proximity to everyone I love for a slower life. I had decided I’d hire help if I needed it so I could focus on my work, but now, my husband and I manage our daughter ourselves while I work from home.

I told myself I’d never work for certain kinds of clients or in certain industries, but I have, because saying yes was the only way to move forward at the time. I said I’d never give up hobbies that felt core to who I am, but some of them haven’t been touched in years.

When people ask my husband and I what it’s like to have left Bombay for Goa, I tell them the truth: It’s great. I like the pace of life here. I can go to the beach on a Tuesday just because I feel like it. I don’t have to factor traffic into all my decisions when I leave the house. But I don’t want to sell it like some fairytale.

The internet loves that narrative: Burn it all down, move somewhere beautiful, and your problems will fade into the sunset. It’s naive. Leaving Bombay was good for us, but it came with its own kind of loss. We miss the people we knew there and the ways our lives overlapped without effort. I miss walking down Colaba Causeway with no agenda. I miss revisiting the restaurants where we had our early dates and sitting at the same tables. I miss ducking into little cafes during the monsoon and shaking the water out of my umbrella. I miss seeing hundreds of new faces every day, the churn of people that makes the city feel alive. I even miss the pointless things like the highways, the street corners, the building gates. All the stuff that formed the background of my life without me realising it.

*~*~*~*~*~*~~*~*~*~*~~*~*~

I interrupt this essay for a little bit of reminiscing via Canva-made picture collages

~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~

Leaving was the right call for us, and leaving hurt. It gave us a better life in some ways, and it shut the door on a version of life we loved. That’s how most big decisions are. Not wins or losses, just trade-offs you learn to live with.

The purity vortex isn’t a lifelong condition for most people. It’s easier to fall into when you’re younger, before your decisions have been tested in wildly different circumstances, when it still feels possible to have found The Right Way to do things.

Of course then life happens and you watch some of your certainties crumble and you change your mind and alter your stance and negotiate your way into adulthood and then what happens? What comes after the purity vortex? Enlightenment? Maturity? Perfectly rational adults making calm, well-informed decisions?

Yeah, no.

I’m gonna call the next one The Halo Complex.

It’s the shift from defending your actions to defending your character. You can’t always defend what you did, but you can almost always defend why you did it.

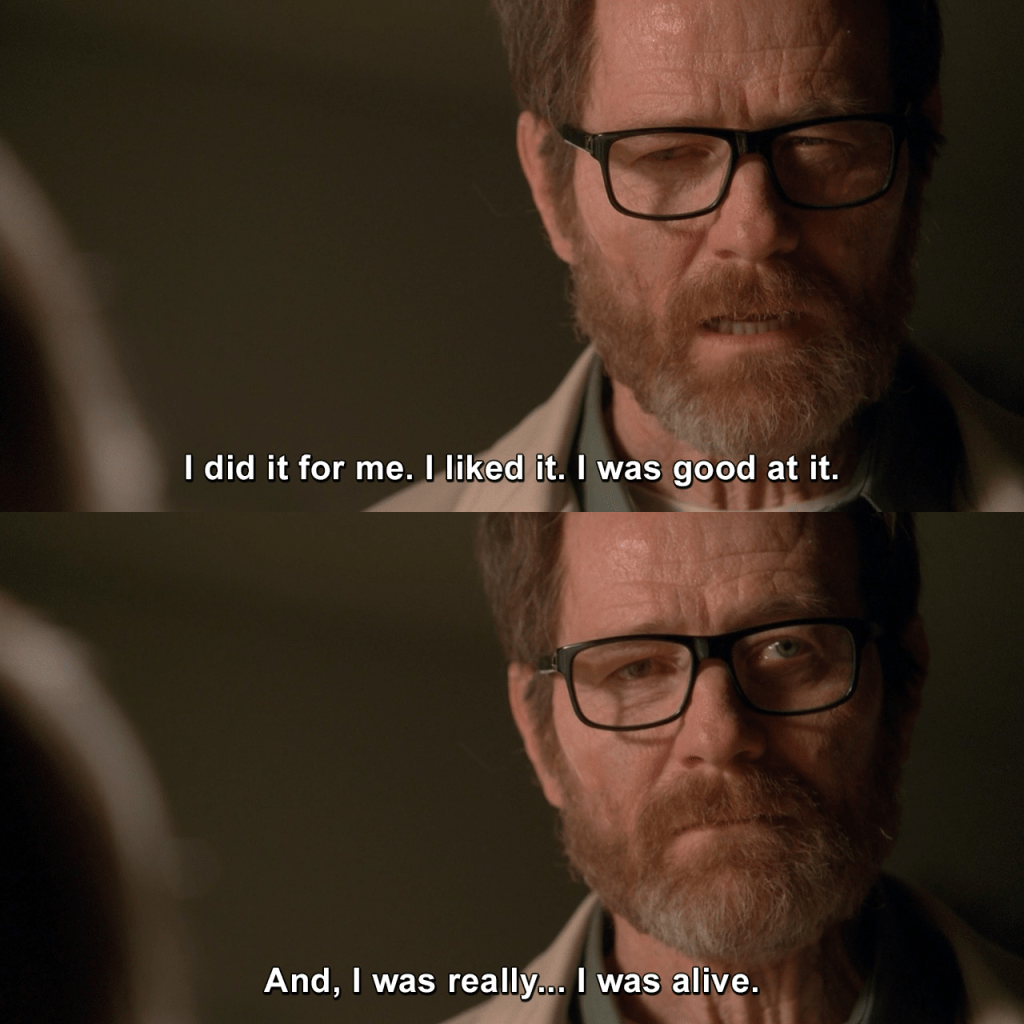

If you’ve ever watched Breaking Bad, you’ve already seen the halo complex in its purest form. Walter White starts out as a high school chemistry teacher with a terminal cancer diagnosis. His plan is to cook meth to leave money for his family after he’s gone. It’s morally questionable but you can at least see the logic. The first season makes it easy to buy into his reasoning. He’s desperate, he’s dying, and he’s doing it to take care of the people he loves.

But as the seasons go on, his motives shift. He’s no longer making meth because his family needs it. He’s making meth because he’s good at it, because he likes the power. And yet, right up until the very end, he keeps that halo shining by repeating the same line: I’m doing this for my family.

Even when it’s obvious to the audience, to his wife, to himself that it’s not true, he clings to the moral cover it gives him.

That’s the halo complex.

The belief that no matter what the evidence says, you are still good. Your intentions were good. You had reasons. And as long as you can believe that, you don’t have to stare too hard at whether those reasons were a little self-serving, or whether you were using them to avoid the truth.

Most of us don’t stay in that headspace for long. It’s exhausting and destabilising. We’re not built to constantly interrogate ourselves. We so desperately need a version of ourselves that we can stand to live with.

If I sit with the possibility that I’ve been wrong for too long, it starts to eat me alive. Most of us are wired the same way. Our brains step in to smooth things over before we spiral. We are nudged back into a version of the story we can live with. We tell ourselves we had no choice, highlight the parts that make us look reasonable, and downplay the rest.

The best you can hope for is a brief window where the story drops away and you see the mess for what it is. Sometimes those windows get forced open: when someone (or the consequences) confront you, when you watch someone else make the same mistake you did, or when you suddenly find yourself on the receiving end of a choice like yours.

When those windows appear, I try to use them. Admit the thing I’ve been avoiding, even if only to myself. Apologise to someone who deserved better, even if it’s been years. Change one small behaviour before the window slams shut again.

I’m not listing these like I’m some wise sage. I’ve done all three, but not nearly as often as I should. Sometimes I use the moment, and sometimes I waste it. That’s just how it goes.

I’m not saying there’s no such thing as right or wrong. There is. I’m saying “right” is rarely the whole story. Most people aren’t purely good or purely bad. We’re all complicated and contradictory and holding onto whatever stops us from feeling like we’ve wasted our effort, or our life.

The point isn’t to tear yourself apart over it. The point is grace. If you can spot the halo complex in yourself, you can see it in other people too. And when you realise everyone’s just trying to make their story livable, it’s a lot harder to write them off as villains.

One of the reasons I love being a Christian is that conviction and grace aren’t in competition. They exist together. Conviction means I don’t get to shrug off the truth when I’ve been selfish or cruel. Grace means I don’t have to be crushed under the weight of it.

The purity vortex is powered by conviction, because you need it when you’re staring down a hard, costly, risky decision. You have to believe it’s the right one just to get through it. The halo complex is powered by grace, which you need to be able to love yourself and love others, even when the facts don’t make it easy. Parents do this with their kids all the time. They see them through a kinder lens than the facts would allow. And most of us need that from each other more than we admit.

I think maybe that’s the thing that makes the purity vortex so seductive when you’re younger. You think moral clarity will save you. But the truth is, moral clarity without grace just makes you brittle. You snap the first time you’re wrong. Grace, on the other hand, will let you look at the mess honestly, take responsibility, and still stay standing. Which, in the end, is the only way you ever get better.

Faith has shown me that both are necessary, but neither is enough by itself. Conviction without grace turns into pride. Grace without conviction turns into avoidance. The goal isn’t to rise above the purity vortex or the halo complex. That’s impossible, and it’s not even the point.

The aim, at least for me, is NOT to get rid of the purity vortex or the halo complex, but to know when to lean on each one without letting them harden into the only story I know how to tell.

If you can hold conviction and grace in the same hand, you’ve already done something rare.

Leave a reply to menezeslynette Cancel reply