This will be the last essay I publish in 2023. It’s essay number 38.

I’ve kept this little heart-driven project alive for nearly ten months now, and it’s hard for me not to get sentimental about the fact that I get to carry it into the new year – tenderly and nervously.

As I wonder what the next year has in store, I remind myself of the fact that calendars are human inventions. Nothing truly changes when one year turns to the next.

That’s not how it feels though.

At midnight on December 31st, whatever opportunity we had to make something come true in 2023, for our community, for the world, and for us – disappears. It’s gone! This realization brings a certain sobriety to the whimsicality often associated with New Year celebrations.

The next year can become anything – but our individual and collective 2023s will be frozen for all time.

And yet again, all of this is made up. The new year is just something we decided is a thing, but that’s never stopped me from taking stock, over and over. I’m quite big on stock-taking.

I’m fairly certain I’ll spend New Year’s Eve in a typical existential quandary, wondering whether 2023 was a ‘good year’ for me. I’ll probably mentally flip through each month, tallying up events in a mental ledger that helps me determine the goodness or badness of the last 365 days.

Am I alone in this annual inventory? I doubt it. But is it really so easy to answer a question like that? Can we distill an entire year into ‘good’ or ‘bad’? For me personally, I might find some middle ground in my answer. But when I think about the world at large, it’s harder.

2023 was a terrible year for the world.

How could any other answer be the case?

Saying the year was ‘good’ can feel shallow, maybe even careless. It would ignore the tears of parents who lost their children at a larger scale than any other ‘war’ in recent past. It would ignore the despair of refugees forced to flee their homes, and the shattered dreams of those who hoped for a better future.

While every year holds some hardship, this year, it felt heavier and more pronounced.

A few weeks ago, we collectively witnessed the surreal un-reality of a temporary ceasefire in Gaza. For seven days, some bombs weren’t dropped. Some guns weren’t fired. Some hostages were released. Some prisoners were freed. And some people that were born in the wrong place at the wrong time didn’t die for no reason.

I’ll never forget how absolutely bizarre the realization was that we, us human beings, could actually stop the bombs whenever we wanted. That we could end the collective punishment whenever we decided to. That we could imagine a different world whenever we chose to.

There are no cosmic laws that make war and violence inevitable. We do that stuff all on our own because we see fit.

This was a year marked by deep and varied struggles that touched every corner of the world. Not just in warzones in Ukraine, Gaza, Sudan, Manipur, The Congo – but in our streets, our political systems, and inevitably, in our living rooms and dinner tables.

During times of global turmoil, I often find solace in the words of Mr. Fred Rogers, a beacon of hope and kindness in a world that feels devoid of both. “Look for the helpers,” he says.

“When I was a boy and I would see scary things in the news, my mother would say to me, ‘Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping.’ To this day, especially in times of disaster, I remember my mother’s words, and I am always comforted by realizing that there are still so many helpers — so many caring people in this world.”

– Mr. Fred Rogers

Mr. Rogers talks about finding those who, despite everything, are working towards a better world. Like in Gaza, the journalists who continued their work amidst starvation, chaos, and danger. The medical professionals that relentlessly, tirelessly mend, repair, and fix broken bodies. The brave men that dig people out of the rubble with their bare hands.

They are the embodiment of optimism and action. When we look for the helpers, we find them everywhere — in the streets, in the news, and in our own homes.

Asking the right questions

Cool so all of this helper stuff is great, but what about right now? What about us? What about the world we’re living in?

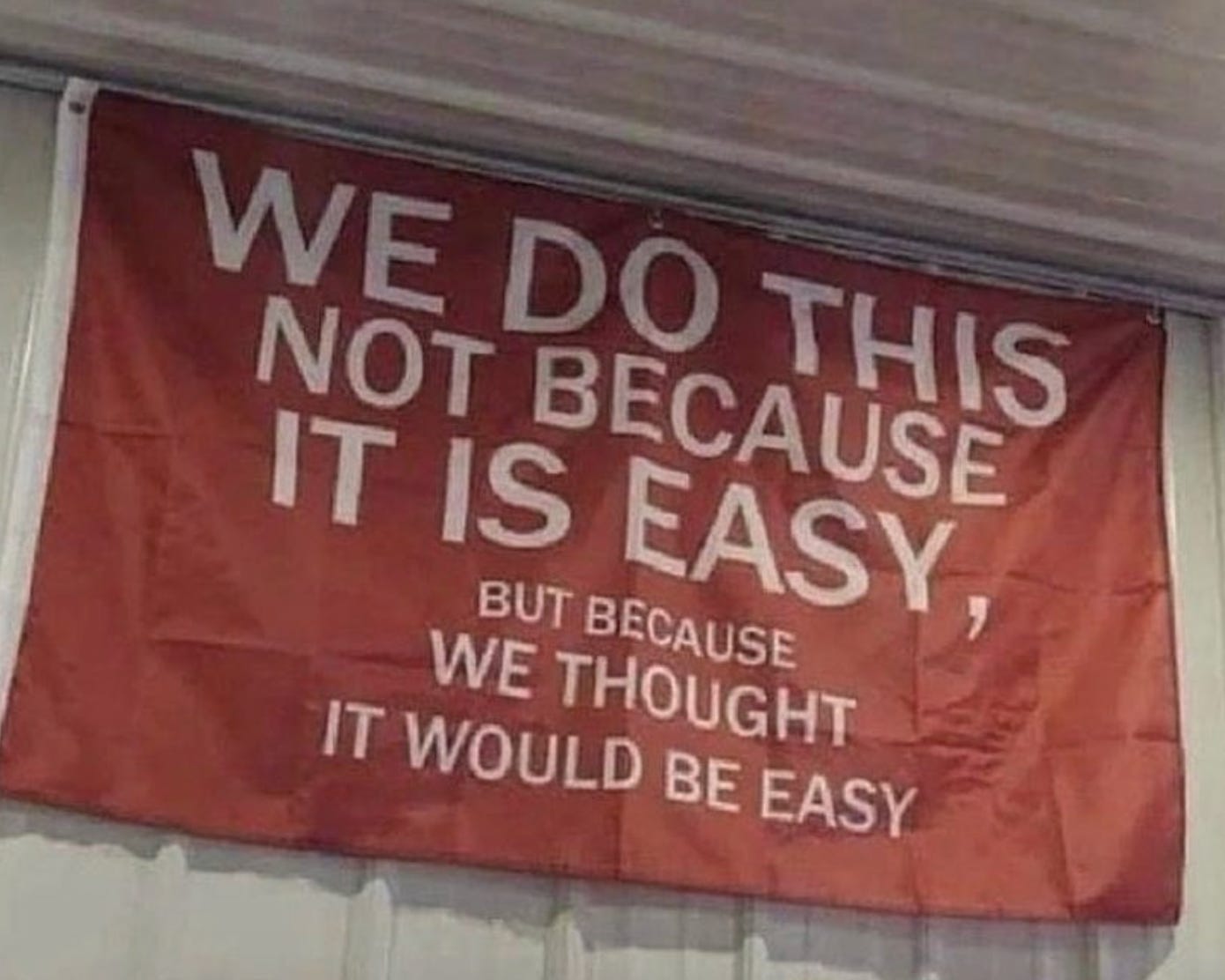

Our history is littered with horrors like the ones we see today, yet we persist, battered and bruised. And then we go on to repeat the same things. So it begs the question of WHY. Why exert ourselves in this relentless struggle to imagine and advocate for a better world?

Is it sheer folly to think we can alter the course of history, to bend the arc of the moral universe just a bit more towards justice by doing our little nonsense? The task ahead feels Sisyphean. An endless, grueling battle against the gravity of human fallibility.

Each time I share a post about the plight in Gaza, part of me scoffs at the futility of it. How could these small acts of digital solidarity possibly influence the hardened policies of an Israeli government bolstered by unwavering support from powerful allies like the United States?

It seems almost laughable to think so. But just like there are wrong answers, I feel like there are also wrong questions. And I think all of these questions might be the wrong ones.

The fact is – if we give up, the answers to our questions about a better world are pre-determined. If the alternative to our collective trying is a world that is all but guaranteed to be filled with grieving parents and preventable death, the question is NOT how we can have the gall to believe that our tiny actions matter.

The question is how we can resign ourselves to the defeat of not trying at all? Will we have the courage to face ourselves if we choose the path of apathy?

Real, significant social change isn’t driven by governments, but by the relentless spirit and collective actions of ordinary people. History is replete with examples that tell us the same story.

The Civil Rights Movement in the United States and the fight against apartheid in South Africa were not victories that landed in our laps courtesy of benevolent politicians. Instead, they were the fruits of relentless struggle, hard-won by the persistence and courage of countless individuals who took to the streets, raised their voices, and dared to demand a better world.

When we talk about change, the true agents are not seated in parliaments or presidential palaces. They are regular individuals who, when united by a cause, become extraordinary, one act of defiance at a time. Governments may draft policies, but it’s the people who write history.

A word of caution

As much as I love inspiring punchlines about the power of the people, I’m also wary of reducing complex realities into overly simplistic or binary views. History teaches us that humanity can rarely be understood through a single lens or narrative. Just like we can’t label a year as good or bad, we can’t do the same for an ideology, a political viewpoint, a social movement, or people in general.

ESPECIALLY celebrities.

Individuals and groups will alway represent a messy mosaic of motivations, actions, and backgrounds. In this light, every judgment we pass, every label we assign, must be scrutinized with a keen awareness of this complexity.

And while this might sound cowardly, contentious, or fence-sitty to some, acknowledging the complexity of reality should not drive us towards apathy. It should just make us better at thinking, listening, and understanding.

The seductive simplicity of a Hollywood-ish narrative – a world of heroes and villains, bad guys and good guys – is mirrored in the polarizing echo chambers of social media, where we are too often pushed to pick sides and defend them without question.

It’s always easier to see the world as full of heroes and villains, but the world we live in is far more intricate, layered, and conflicting. It’s crucial to understand that one aspect of an event doesn’t negate the others, it just makes it more complex.

Society isn’t manipulated just by clear-cut bad guys. More often than not, it’s enacted by those perceived as ‘good.’ And this manipulation isn’t some big scary conspiracy; it’s an inherent feature of the system in which we live. It’s a system designed to protect itself.

Political satirist CJ Hopkins puts it perfectly in his essay:

“Ideological systems are organic entities, self-sustaining organisms, with survival programming, just like you and me. They react when threatened, like any other organism, like our bodies react to mutating cells, invasive pathogens, and other internal threats.

They perceive (or register) these threats, and take defensive action against them. The more totalitarian the ideological system is, the more aggressive its reaction to internal threats will be.”

But we have to believe in a world where life has value

Amidst this whole chaotic backdrop, one truth remains clear and unassailable: we must believe in a world where life has value. In 2023, this stance might seem radical, but the urgency of our times demands it.

Our present circumstances have laid bare a disturbing truth: for too many, life is viewed as conditionally valuable. The rhetoric emanating from government podiums, justifying wars and unfettered violence, reflects this grim reality.

This mindset, that some lives are inherently less worthy, has been the catalyst for some of the darkest chapters in our history. It’s a corrosive belief, one that eats away at the very core of our humanity. It’s a belief we must challenge, not just in words, but in our daily actions.

And somehow, all this coming from me feels a little (very) tone-deaf. I sit quite comfortably at the intersection of many privileges. I live in a comfortable home, I don’t come from any marginalized group as such. I recognize that my viewpoint is shaded by layers of insulation from the very atrocities I condemn.

This isn’t pointless self-flaggelation, but a super important admission. One that shapes not only my understanding but also my approach to thinking and talking about these issues. This isn’t where my journey ends, but where it earnestly begins.

Advocating for the equal value of every life is not idealistic; it is imperative. Recognizing this truth should not ignore the necessity of accountability and justice, instead it’s humbly admitting that a truly just world cannot be built on the suffering of others. We cannot secure peace for ourselves by sowing seeds of unrest somewhere else.

I’m carrying this perspective with me into the new year.

This is not a call to heroism, but a call to be human: to recognize, respect, and respond to the humanity in others. I’m living with the conviction that helpers exist everywhere. And I’m committing to being a helper too. The actions of helpers –– whether it’s advocating for others, raising families well, being generous and compassionate, going to work, and building a life –– their actions contribute to the reality of a more compassionate world.

The kind I hope to live in next year.

Leave a reply to The Guilty Pleasure of Being Angry – Unfinished Conversations Cancel reply