Hi!

And to everyone still here reading this – hello, how are you.

It’s December, and for all my readers, you know what that means!!!!! Except that you don’t because this is our first December together, this little community of 14 of us that includes my entire family who have no way to escape.

I’ve decided that this month is about storytelling, which is the practice of telling stories to keep people engaged enough so that they can save money on Netflix subscriptions and things like that.

Today’s story, by definition, is almost too good to be true. Here’s why:

- It was a SERIOUSLY amazing thing that happened.

- People began wondering if such an amazing thing could ACTUALLY happen in real life and hence began questioning the possibility of it ever happening at all.

But it is a true story. There are photos, letters, and references to it. And there is, obviously, an article in TIME Friggin Magazine that talked about it too.

Okay, gather ’round, and I’ll tell you.

“I ask that the guns may fall silent at least on the day the angels sang.”

– said Pope Benedict XV, who became the Pope only a month after the First World War broke out, which undoubtedly makes for a very difficult stint at a new job.

The war had been raging on for four months at the time, which was already four months too long. Not by war standards, but by what-was-promised-to-the-people standards. Everyone at the time believed that the fighting would be over by Christmas that year, but sadly, in the trenches, the war was barely getting started.

The year was 1914. One hundred and nine years ago.

Today when we say that we’re ‘in the trenches’ we’re usually describing gruelling and difficult things – e.g. being in the trenches of postpartum. Or ‘Oh how’s work? Ahh it’s the end of the month so we’re really in the trenches, you know?’

But I assure you, nothing that you or I could ever describe as ‘the trenches’ comes remotely close to the ones in this story. If you want, you can skip the next few paragraphs because the trenches were bad and you might not want to be transported there during this story time.

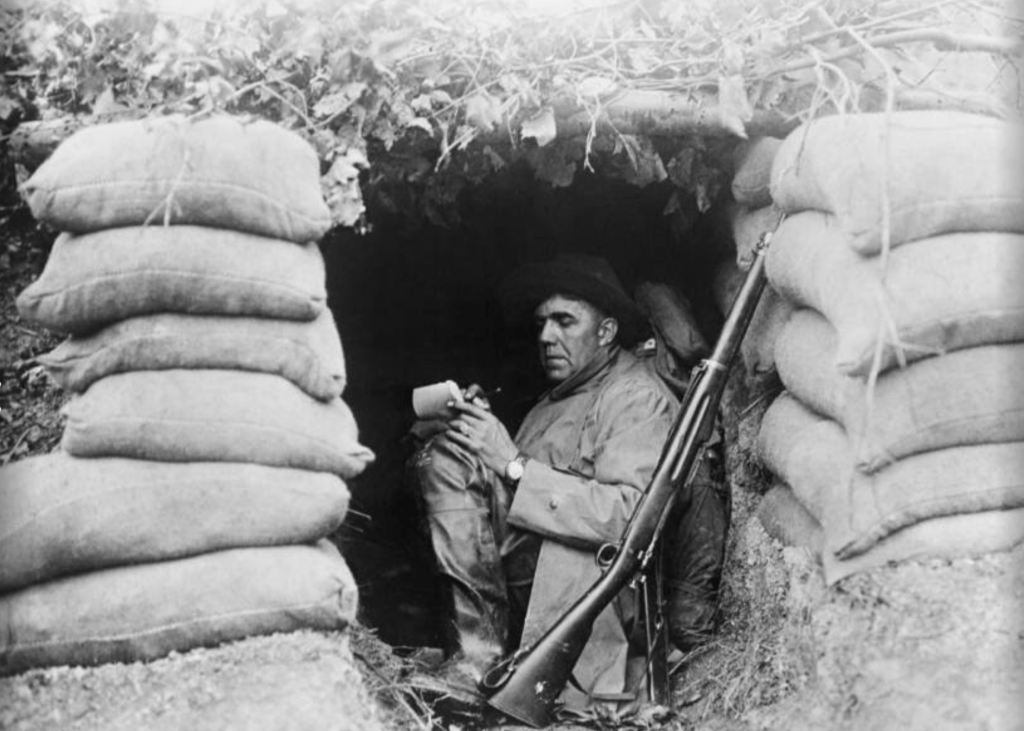

Trench warfare during the First World War was grim and harrowing. The trenches were a network of narrow, muddy corridors, often no wider than a few feet. They were dug all across the Western Front, which extended through several countries in Western Europe. The trenches were usually waterlogged, and infested with rats and lice.

They were lined with sandbags and barbed wire, with boards laid down in an attempt to keep soldiers’ feet dry. But rain and poor drainage systems usually led to them being waterlogged anyway, creating a breeding ground for diseases like trench foot, a painful condition caused by constant exposure to damp and unsanitary conditions.

The trenches were cramped, forcing soldiers to live and sleep in confined, uncomfortable spaces, with little protection from the freezing cold. They lived in a perpetual state of alertness, with the ever-present sound of gunfire and the fear of an enemy raid or gas attack.

The psychological toll was immense, with many soldiers suffering from ‘shell shock’, now known as PTSD, due to the constant stress of trench warfare. Combat happened between these trenches, which were located so close to one another that soldiers from either side could actually shout audible insults at one another.

Above the trenches, in full view, lay No Man’s Land – a desolate expanse of barbed wire, shell craters, and the bodies of fallen soldiers. This stretch of land was a deadly battleground where many lost their lives.

Time was a blur in the trenches.

But outside the trenches, it was early December 1914, and the new Pope issued an appeal to the leaders of Europe “that the guns may fall silent at least upon the night the angels sang.” His hope was that a ceasefire would allow the warring countries to possibly find a way to make lasting peace, but his call fell on deaf ears and hard hearts.

The weather that December was exceptionally cold and wet. Many of the trenches were continually flooded. Soldiers were covered in mud and exposed to frostbite and trench foot that seemed impossible to get rid of. They were dreading having to spend Christmas away from their families.

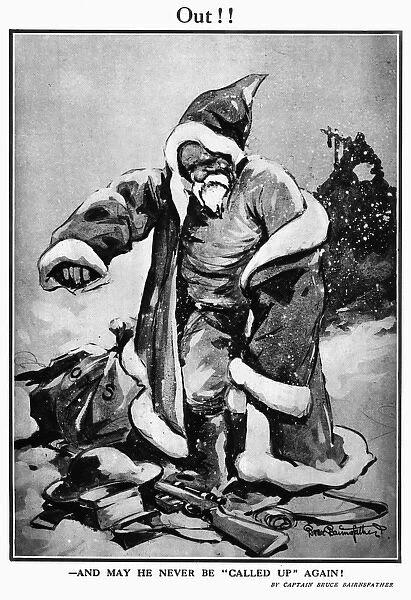

In a letter to his family, a British soldier-turned-cartoonist (love that for him!) named Bruce Bairnsfather said:

“Here I was, in this horrible clay cavity, miles and miles from home. Cold, wet through and covered with mud. There didn’t seem the slightest chance of leaving — except in an ambulance.”

Bruce Bairnsfather

And he was right. As Christmas approached, it was clear that nobody was leaving the trenches, in spite of the Pope’s appeals. With that in mind, soldiers began receiving letters and care packages from their families. These packages often included food, clothing, and small gifts.

Time was a blur in the trenches.

But it was finally Christmas Eve. Soldiers began unwrapping gifts from home. The German Emperor William II, in an attempt to boost morale, had sent Christmas trees to the regiments, along with candles.

“It was a beautiful moonlit night, frost on the ground, white everywhere,” reported Private Albert Moren. “At about seven or eight in the evening there was a lot of commotion in the German trenches and there were these lights – I don’t know what they were.”

What happened next changed everything. The Germans broke into song, singing the carol ‘Silent Night’ or ‘Stille Nacht’.

“I shall never forget it; it was one of the highlights of my life. What a beautiful tune,” recalls Moren. Soon, voices from the British side responded with Christmas carols of their own.

“First the Germans would sing one of their carols and then we would sing one of ours, until when we started up ‘O Come, All Ye Faithful’ and the Germans immediately joined in singing the same hymn to the Latin words Adeste Fideles. And I thought, well, this is really a most extraordinary thing – two nations both singing the same carol in the middle of a war.”

Graham Williams of the Fifth London Rifle Brigade

Eventually a German soldier yelled out, ‘Tomorrow you no shoot, we no shoot’.”

The next morning, on Christmas day, soldiers popped their heads out the trenches to double check and confirm whether that promise still stood. And slowly, but surely, they began to emerge from the trenches. And for the first time ever, they began to congregate in No Man’s Land. People who had just recently been engaging in deadly warfare, now shook hands, exchanged gifts, and greeted one another.

Corporal John Ferguson later recalled the events of that morning: “What a sight – little groups of Germans and British extending almost the length of our front! We could hear laughter and see lighted matches, a German lighting a Scotchman’s cigarette and vice versa, exchanging cigars and souvenirs.”

The Christmas truce had begun.

A British soldier shared this account

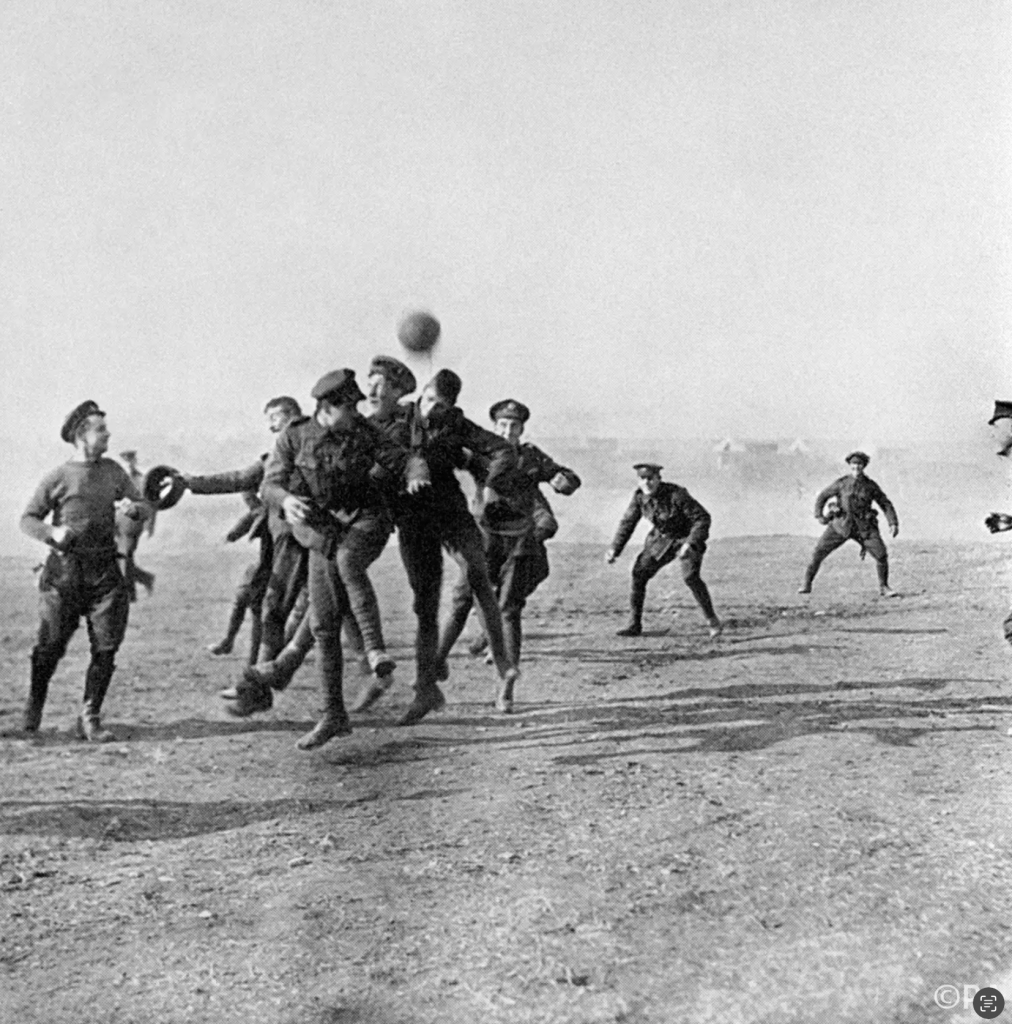

“We exchanged cigarettes and goodies with the Germans, and then from somewhere, somehow this football appeared! We didn’t form a team, it wasn’t a team game in any sense of the word. It was a kickabout, everybody was having a go. It came from their side; it wasn’t from our side where the ball came. I had to go at it, I was pretty good then, at 19.”

Ernie Williams

Many, many years later, this football game was verified in another diary account by a German Lieutenant.

“Eventually the English brought a football from their trenches, and pretty soon a lively game ensued,” he wrote. “How marvelously wonderful, yet how strange it was. The English officers felt the same way about it. Thus Christmas, the celebration of love, managed to bring mortal enemies together as friends for a time.”

Kurt Zehmisch

There were stories of former barbers giving soldiers haircuts, and pork roast being shared as a meal. There were stories of people helping each other bury their dead. Soldiers with cameras captured these moments because of how unusual they were. On that Christmas in 1914, people from both sides put down their weapons, stepped out of their trenches, and met in the middle. And for a brief, beautiful moment, there was peace.

By January the following year, news of the truce made its way to the newspapers, and numerous stories, letters, and photographs were published. But of course, it was only ever a truce, not lasting peace like soldiers and their families had hoped for.

“The first German who came along threw his arms around one of our chap’s neck and kissed him. It was surprising to see the German soldiers – some appeared old, others were boys, and others wore glasses. Some of them even went as far as to state they would not shoot so long as our regiment was on that particular set of trenches. A number of our fellows have got addresses from the Germans and are going to try and meet one another after the war.”

Pvt. Farnden, Rifle Brigade

I wish this story ended differently, but we already know how history played out. There are rarely any happy endings. It would be another three Christmases, with a staggering 15 million lives lost, until the war finally ended.

And in all that time, there was never another truce like the one on Christmas in 1914.

The truce wasn’t just an example of goodwill during a dark time, but it cemented the fact that those on the ground, rather in the trenches, are rarely ever fighting the same battle as those in command. It exposed an inherent conflict within a conflict – soldiers, despite being entrenched in a battle fueled by nationalistic fervor, found common ground with the very men they were supposed to despise. And together, they simply sought a break from the hardship of war.

Unsurprisingly, one of those who strongly criticized the truce was a young Adolf Hitler, then serving as a dispatch runner. He saw the fraternizing with the enemy as a betrayal of national conduct. “Such a thing should not happen in wartime,” he reportedly said. “Have you no German sense of honor?”

After Christmas, the war’s grim reality quickly returned to the Western Front. The truth is the truce only happened because lower-ranking officers on both sides allowed it. The higher-ups in the British and German military did their best to make sure nothing of the sort ever happened again.

“Really you would hardly have thought we were at war. Here we were, enemy talking to enemy. They like ourselves with mothers, with sweethearts, with wives waiting to welcome us home. And to think within a few hours we shall be firing at each other again.”

Gunnar Masterson

Today, as we stand at the threshold of another Christmas in the shadow of ongoing wars and conflicts, what can we take away from the Christmas Truce? Perhaps it’s the understanding that peace, no matter how fleeting, is always possible.

Or maybe it’s the recognition that beneath the uniforms and the flags, behind the rhetoric and propaganda, we are all human, longing for a moment of understanding and a break from the turmoil. Or it’s a realization that sometimes, the most profound acts of rebellion are those of empathy.

Most significantly for me, it’s the fact that the truce was not born from stupid useless diplomatic boardrooms, but from the trenches of common soldiers. In the mud, under a cold and freezing sky. A testament to the power of commonality. That Christmas in 1914, soldiers on opposing sides recognized each other not as faceless enemies, but as fellow humans caught in the crossfire of geopolitical agendas.

And amidst even the most dehumanizing conditions, a profound sense of shared humanity can still make its way through, but on a silent night.

“I ask that the guns may fall silent at least on the day the angels sang.”

#CeaseFire

Leave a reply to Valencia Aguiar Cancel reply