Ever since I found out I’d be having a C-section to bring my daughter into the world, the thought of the painful morning-after-surgery simmered in the back of my mind.

Since it wasn’t my first major abdominal surgery, I knew that taking those first steps would be gut-wrenchingly painful – literally. Childbirth, in any form, is one of the hardest things a person can do.

Because although you’ve been cut open, meddled with, stitched up, hooked onto an IV and a catheter. And although you’re dazed and in pain and confused and disoriented, you’re STILL not the most vulnerable or helpless person in the room.

There’s a baby that needs you.

That’s why when the next morning came, I couldn’t sit and wallow and feel sorry for myself. I gathered all my courage, not even 24-hours after my surgery, and I walked hunched over from my hospital bed to the bathroom to have a shower. It was remarkable how a warm bath – entirely painful and unnecessary – made me feel SO much better. It was wonderful. I was clean! I could change into my own clothes and abandon the hospital gown.

I hobbled back to bed feeling twenty times better than when I had hobbled out only moments before, and had only one request for my mother: Can you please pass me the lipstick from my bag?

My body, having just undergone the monumental task of bringing a new life into the world, felt completely alien. I was struggling to anchor myself to something familiar, something distinctly ‘me’. I wrote about this in my previous essay, but makeup has become a ritual for me. I don’t start my day without getting showered, dressed, and ready. Makeup on and all.

So in a hospital room, while recovering from childbirth, the decision to wear lipstick was not about vanity or the gaze of others. It was a gesture towards normalcy, a way to bridge the gap between the person I was the day before, and the new identity I was slowly figuring out.

I needed that lipstick. I needed it for me.

And in the months to come, I kept up the routine. It didn’t matter whether I was exhausted, whether someone else had to watch my daughter in the five extra minutes it took me to wear my makeup (I’m really quick!). It didn’t matter if I wasn’t even leaving the house – I stuck to my routine of wearing makeup in those blurry postpartum months.

But I also thought deeply about it.

There are many routines that become a part of your life that change or evolve as your life changes and evolves. For example, I used to wake up super early in the morning when I had to catch a train to go to work. There was NEVER a time where I didn’t have my alarm set for 7 am. Now that I work from home, I’ve let go of that routine, even though waking up early came with many tangible benefits.

Here’s another one: Before having a baby, I used to spend the first half of my day working and ticking off all the big stuff on my to-do list. Now, the first half of my day is spent running around with a toddler, and I work at night. Sometimes into the early hours of the morning.

Most of these routine changes are born out of convenience or necessity. But wearing makeup is neither convenient, nor is it necessary. So why hasn’t it evolved into something else? Why hasn’t it changed? A lot of these questions prompted me to accept some harsh truths about beauty culture and understand my own relationship with it.

Why did I need the reassurance of makeup to feel like myself right after having a baby? In a situation where external appearances should have been the least of my concerns, why did a beauty ritual hold such significance? Was I trying to adhere to beauty standards? NO. I was adhering to my own standards.

Adopting beauty standards as your own is a thing

When you adopt the standards of something or someone else as your own, it’s nearly impossible to analyze your choices objectively. For example, if anyone insinuated that I wore makeup to impress men, I would openly scoff at them. I simply do it for me, so that I can feel good, and confident, and beautiful.

But as I said in part one of this series, these truths should start a conversation, and not end it. It can’t simply be: I wear makeup because it makes me feel good. Period. We have to ask ourselves WHY. And when I did, the only answer I could come up with was: Because it’s a choice I make, and this choice makes me happy. Period.

Okay but WHYYY? Why did I choose this? And why does it make me happy?

Wearing makeup at home alone does not prove that I’m doing it for myself. It proves that I’ve taken on cultural beauty ideals as my own ideals. It proves that I’ve adopted beauty standards as my own standards.

The myth of the self-made choice is just that – a myth. It’s a comforting narrative that masks the uncomfortable truth of our constrained agency. We’re led to believe that because we’re choosing something out of our own free will, that it’s an empowering choice. But that’s a false belief.

The illusion of choice in beauty culture

Neoliberal feminism and choice feminism are two closely related ideas, each emphasizing personal choice and individualism, especially in the context of a capitalist society.

Neoliberal feminism highlights women’s individual accomplishments and choices as signs of feminist success. This approach emphasizes personal choice within the existing economic system, rather than pushing for broader social changes that might benefit all women.

Choice feminism takes this a step further by suggesting that any decision a woman makes is feminist simply because she has made that choice herself. This idea is especially prominent in the beauty industry. For example, the act of wearing makeup is often portrayed as an empowering choice, a symbol of freedom and personal expression.

However, this overlooks the possibility that such choices might be influenced by social pressures or beauty standards, rather than being purely self-driven. This concept suggests that any choice, no matter how influenced it may be by societal expectations, is an expression of feminism if a woman decides to make it.

What neoliberal feminism looks like

Career success: It celebrates women climbing the corporate ladder or becoming successful entrepreneurs as signs of feminist progress. For example, a woman becoming a CEO of a Fortune 500 company is seen as a victory for all women.

Financial independence: It advocates for women’s financial autonomy, viewing personal wealth and the ability to participate in consumer culture as empowering. E.g. buy ALL the things, you’ve earned it, girl. You don’t need a man to buy you stuff. YOU buy it for yourself. But make sure you BUY it okay? Pls? We need your money. You deserve nice things.

Lifestyle and appearance: This includes choices like wearing makeup, getting plastic surgery, or dressing in a certain way. These choices are seen as empowering acts of self-expression, regardless of the social pressures that might influence them. Let’s say with oppressive beauty standards that require women to look young in order to be beautiful and powerful, you can simply take control of the aging process, take control of the narrative, get the fillers and botox, and effectively, oppress yourself before anyone else can. Same goes for makeup btw.

What neoliberal feminism usually ignores

Systemic inequalities: It tends to overlook broader social, economic, and political structures that perpetuate gender inequalities. Issues like wage gaps, labor rights, and systemic discrimination often receive less attention. It doesn’t engage with the reasons behind WHY women, in general, have less access to high-paying jobs

Collective action: There’s a lack of focus on collective action or social movements. E.g. the focus might be on a woman starting her own business as a symbol of empowerment, while the importance of those fighting for paid maternity leave is understated.

Intersectionality: Neoliberal feminism lacks an understanding of how different issues like race or class might intersect and affect women’s experiences differently. E.g. it might not fully recognize how an Indian woman’s experience working in a research lab in North Carolina differs significantly from her white counterpart due to racial discrimination.

I’ve been asking myself this question: Is the choice to wear makeup genuinely mine, or is it a conditioned response to the fact that wearing makeup grants me access to the things I want? Do I like makeup for makeup or because it helps me look good in a world that rewards good looks?

Systemic patriarchy doesn’t vanish simply because we label our choices as self-driven. In a world still dominated by male perspectives, many women don’t have the luxury of making truly autonomous choices. Their decisions are often dictated or heavily influenced by their environment, whether it’s workplace, societal norms, or authoritative figures in their lives.

Everything is empowering

“Everything Is Empowering. Everything! Bronzer, Botox, breast implants. Lip filler, facials, foundation. Everything Is Empowering because everything is a choice, and feminism is all about women getting to choose stuff, right? You see, “concealing your flaws” because you choose to conceal your flaws is very, very different from “concealing your flaws” because the media tells you to. Now it is Empowering.

But there is a caveat to this clause and that caveat states: Everything Else Is Shaming. Everything! Questions, comments, curiosity.

Everything Is Empowering and Everything Else Is Shaming is a convenient narrative for the beauty industry because it allows us to cling to the comfortability of beauty standards while claiming “feminist” ideals. Here’s where that falls apart: Feeling empowered is not the same as being empowered. Beauty isn’t about being worthy of the male gaze anymore, it’s about being worthy of one’s own gaze.”

I began understanding the truth behind this thanks to – you guessed it – some comments I saw on an Instagram reel. There was a parody video of things that a pick-me girl would say to someone that wears makeup.

I found it pretty funny because, as a girl that wears makeup, I’ve gotten a lot of comments like those too:

“Wow, I could never find the time to wear so much makeup.”

“How do you wake up so early to do all this, I could never.”

While I don’t necessarily think these comments are offensive, I can quickly tell when they come with a sense of condescension or judgment at my vanity. So anyway, I headed over to the comments section of this reel, for research purposes obviously, to see what was up.

No surprise, I found a comment by a girl that says she doesn’t like wearing makeup for reasons entirely justifiable to her, and she proceeded to get ATTACKED by everyone else. Most of the replies were: Why are you shaming women? Why do you think you’re better than us? You must be a sad, trash human being.

Now sure, her comment was on the spicy side of things. She implied that makeup isn’t a creative outlet when it can be, or that it takes away from a woman’s ability to pursue other creative outlets, which isn’t necessarily true. I don’t love how she worded her opinion, but I don’t believe in tone-policing either.

So what made everyone SO ANGRY with her? Why did she, as the children say, get ratioed?

I think it’s partly because feminism has now attempted to render certain things off-limits for criticism. It’s hard to comment on, question, or criticize a woman’s choices, without quickly being called a misogynist.

But what makes me so annoyed about this style of thinking is that it misses an important caveat: Just because a woman has the option to choose doesn’t mean that the choices available to her are free from exploitation. Choices are always made within the limitations of certain systems. Always pay attention to the systems in which choices are made!!!

Just because a woman chooses to access power through good looks, it doesn’t mean that she’s making a choice that empowers all women. It doesn’t mean that the power she gains access to can override institutionalized power structures.

When different privileges intersect, pretty privilege does NOT come out on top. As a result, the idea of empowerment that’s sold to us, whether it’s makeup, botox, or dressing a certain way, can sometimes feel more disempowering than liberating.

Good for me, bad for the collective

It’s possible to make a choice that benefits you, and is the right choice for you – but this personal gain comes with a collective cost.

Each time I conform to beauty standards, say, as a mom, I’m reinforcing them. By looking dolled up, I’ll usually get comments like: “Woah, you don’t look like a mom.” Implying that other mothers who might not prioritize a makeup routine – look more like a mom? Meaning they look tired? Or like they don’t have time to ‘take care of themselves?’ Or that they look unkempt? Haggard? Are those not problematic stereotypes for mothers to begin with!!!! (don’t send me down that rabbit hole please please please.)

By upholding and personifying these beauty standards, I’m an active participant in a system that devalues those who don’t fit into its narrow, exclusionary criteria. It’s a painful acknowledgement: my pursuit of beauty, while beneficial to me, perpetuates a culture of discrimination, a culture that equates worth with appearance, a culture that systematically sidelines those who diverge from its prescribed aesthetic.

It’s good for me, but it’s bad for the collective.

I hate writing all this. I love feeling like a shiny diamond of a human being at the end of my essays. I love patting myself on the back for how self-aware and wonderful I am. I like it EVEN MORE when others do it for me. But here I am, standing at a moral crossroads, fully aware that I am very much part of the problem. I’m complicit in a system that I intellectually and morally oppose.

Yet, the thought of giving up whatever power I have is terrifying. In a world where appearance is inextricably linked to social capital and acceptance, can I afford to let go of this advantage? Um, no I cannot.

I don’t want to. It’s too scary. I’m too scared. I might also be too selfish. Especially as I grapple with the evolving identity of being someone’s mom, (which trust me, is not very high up the social capital ladder), I’m scared of becoming invisible. Or less relevant.

I know I have more to offer than just good looks, but also, what if I don’t? At the very least I can serve lewks 🔥🔥 The thought of not having good looks to fall back on is too overwhelming. I’m not ready to relinquish the privilege that beauty and makeup afford me.

I’m not trying to pointlessly beat myself up here. We can recognize the harm of certain societal norms, yet find ourselves unable to, or unwilling to break free from them. This is annoying, but also normal.

But I love beauty. We all do. And that’s great!

I feel like I’ve been talking about beauty like it’s a bad thing. I don’t for a second think beauty is the problem. I love beauty. I’ve written essays about beauty in various forms: Beautiful sounds, beautiful friendships, beautiful memories, beautiful responsibilities, beautiful uncertainty.

And I’m not unique in my love for beauty. Humanity loves beauty. Our love for it is more than just a fleeting fancy, it’s ingrained in us. We’re innately drawn to beauty, captivated by its allure, and inspired by its presence. Beauty, in all its forms, is worth seeking.

When you’re captivated by a beautiful painting or a soul-stirring song, it’s not just the canvas or the colors that grab you. It’s not the particular chord progression or melody. It’s the emotion it evokes, that ineffable ‘something’ that resonates deep within you.

True beauty, like art or music, can’t be boiled down to its physical attributes. The whole is greater than the sum of its parts. It’s something profound and personal. So yes, I love beauty. We all do. And that’s perfectly fine as long as we don’t lose sight of the more substantial forms of beauty that enrich our lives and feed our souls.

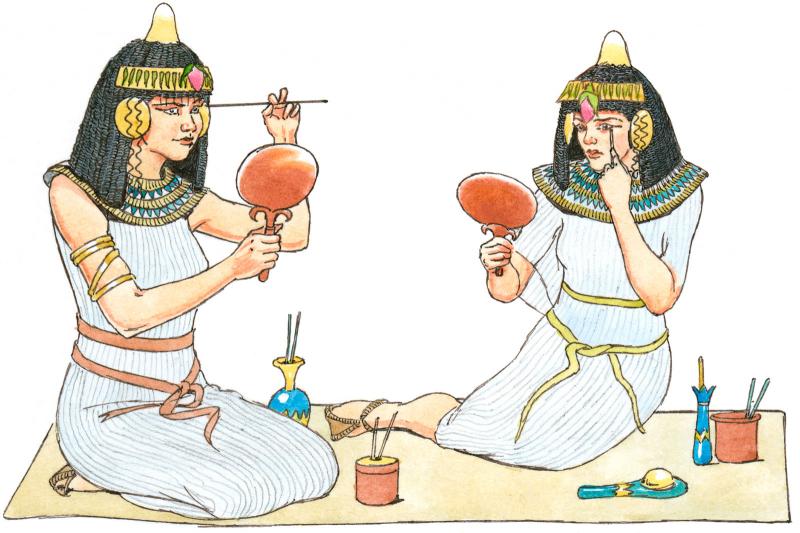

Throughout history and across cultures, beauty routines have always existed. The ancient Greeks developed cosmetics, in fact the word comes from the Greek word ‘kosmetikos’. The ancient Egyptians literally pioneered cat-eyeliner, and buried their dead with a bunch of makeup.

Makeup was used to signify social status in 1600 BC in China. In India, henna has been used for centuries to commemorate special occasions.

My point is that beauty routines existed to communicate something to people on the outside – in short, they were done for others. Nobody was fooled into believing they were doing it ‘for themselves’.

The hardest part about all of this

My daughter is now a curious one-year-old, and she watches me apply my makeup each morning, her wide, adoring eyes follow every motion. This quiet observance, innocent as it seems, is laying the groundwork for a conversation we are yet to have.

One day, I’ll sit down with her and explain that makeup, while a delightful form of self-expression, isn’t a necessity. I’ll tell her that it’s a choice, one that can be embraced or ignored. I’ll tell her that nobody truly NEEDS it. I’ll teach her that makeup can be an art, a joy, a statement, but never a measure of her worth.

But will she believe me? Why should she?

My daughter’s understanding of beauty will be shaped not only by my well-intentioned words, but my actions too. I hope she learns to navigate her own path in beauty and identity, drawing from my experiences but not feeling confined by them.

I hope that she can redefine beauty for herself in ways I never could.

Leave a comment